CHAPTER VIII

THE TECHNIQUES OF TRACTION AND MANIPULATION OF THE SPINE

The purposes of manipulation of the spine are:

1. If the patient is suffering from his first attack of spinal pain, the aim is to snap as many as possible of the fibrillae in the nucleus and so to increase the volume of the globule of nuclear jelly in the posterior part of the nucleus. An appreciable increase in volume sharply reduces the pressure exerted by it on the posterior wall of the annulus.

2.If the pain has been present for more than three weeks, or if it is an acute exacerbation, manipulation secures relief of pain by moving the fibrous nucleus away from the posterior part of the annulus. Moreover, it slows down the erosion of the annulus; and repeated manipulations aid in the process of grinding up the nucleus.

3.Manipulation almost always confirms the diagnosis of a nuclear lesion. If the patient's condition remains unchanged or deteriorates it points to the operative removal of the nucleus or to another diagnosis.

TRACTION

Manipulation can be carried out satisfactorily without any apparatus. I suggest that the doctor should manipulate his patients with spinal pains for six months before getting traction apparatus. But, traction is a valuable aid. It increases the volume capacity of the nuclear space. In the first attack of backache it helps to fracture fibrillae; and in later attacks it tends to suck the fibrous nucleus to a more central position, i.e. away from the sensitive posterior part of the annulus.

The doctor himself must do the manipulations, assisted by his office nurse. He knows (or soon learns) what he wants to do and how to do it. To refer the case to a physiotherapist is simply transferring the patient to the hands of another lay manipulator. Women are rarely strong enough to manipulate a spine adequately. In fact, the best operators are big and powerful men. It is not a gentle art. Manipulation of the cervical spine in a patient with an eighteen inch neck will tax the strongest man and equivalent force is used on the other regions of the spine. Force must be used judiciously, however, in children, slightly built people and frail or elderly people. Movement of the fibrous nucleus away from the posterior annulus is indicated by a snapping or clicking sound and an attempt is made on each movement to elicit this sound.

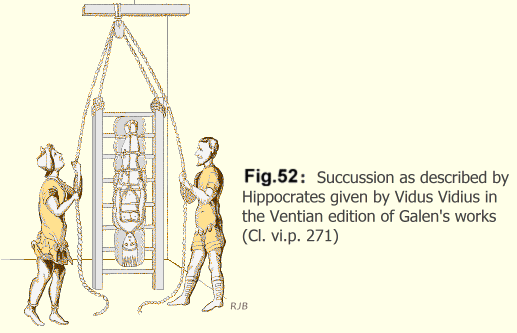

It is interesting to note that Hippocrates described traction and manipulation which in principle is the same as the method we use. He described the ladder and the method of tying the patient to it. "The ladder is placed on the ground. The ankles are fastened securely to the ladder and in like manner, he is further secured both above and below the knee and also at the nates. The trunk is not secured because to do so would interfere with the effects of the succussion. The arms are to be fastened along his sides to his own body and not to the ladder. When matters have been arranged thus the ladder is hoisted up and succussion (i.e. shaking the spine) is applied." (Fig. 52).

Hippocrates added, "This device, however, is an old one and I give great praise to him who first invented it."'

He also described the intervertebral disc as "being formed of nervous tissue and cartilage united together by a pulpy and nervous mass originating from cartilage" - a more significant description than any contained in modern text-books of anatomy.

CERVICAL SPINE

MANIPULATION WITHOUT TRACTION APPARATUS

If the patient has poor teeth or false teeth he may be unable to tolerate the traction apparatus. Also young and old patients, particularly, can be adequately treated without apparatus.

Rotation:

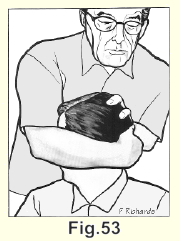

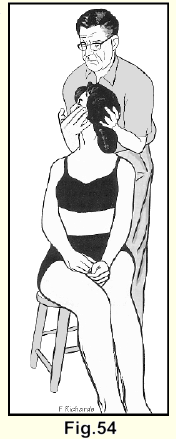

In most cases a headlock (Fig. 53) is used by the operator, who stands behind the patient. If the patient is small or frail the operator places one hand under the jaw and the other under the occiput. (Fig. 54). With either grip traction is applied by lifting the head up.

With the cooperation of the patient the head is rotated as far as it will go to one side and the manipulation is completed with a forceful snap. The same procedure is done in the opposite direction.

Posterior:

The operator uses both his thumbs to manipulate the spine posteriorly, one thumb being over the other, and as he thrusts forward on the spinous processes one after another, the whole cervical spine is manipulated. While the posterior manipulation is carried out, the nurse places both hands on the patient's forehead, or one hand on the forehead and the other on the chest, and thrusts backwards as the operator presses the spinous processes forward (as shown in Figure 62 but without the head halter).

Lateral:

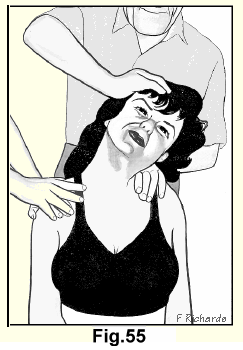

The patient is asked not to lift his shoulder and to aid, rather than

resist, the movement. The operator's second metacarpophalangeal joint

is pressed behind the transverse processes of the lowest cervical

vertebrae.

With the patient's cooperation, the head is pushed

sideways and somewhat backwards with one hand while the other hand

presses forwards and medially, and the manipulation is completed with

a short strong jolt. The other side is done in the same way. The

nurse applies counter-force to each shoulder in turn (Fig. 55).

With the patient's cooperation, the head is pushed

sideways and somewhat backwards with one hand while the other hand

presses forwards and medially, and the manipulation is completed with

a short strong jolt. The other side is done in the same way. The

nurse applies counter-force to each shoulder in turn (Fig. 55).

ON TABLE TECHNIQUE

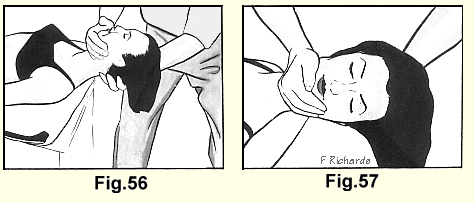

If the doctor prefers he may perform some movements with the patient lying face upwards on the examining table, the shoulders being level with the end of the table. The nurse applies countertraction by grasping the patient's ankles (Fig. 56).

Rotation:

The operator places one hand under the occiput and the other under the jaw and while applying traction, rotates the head as far as it will go to one side and completes the manipulation with a forceful snap. The same procedure is done in the opposite direction. (Fig. 57).

Posterior:

The operator applies traction to the neck and thrusts forward with his knee on the cervical spinous processes and thrusts backwards with his hands (Fig. 58).

Lateral:

This procedure is performed as described previously, the patient being seated on a low stool (Fig.55).

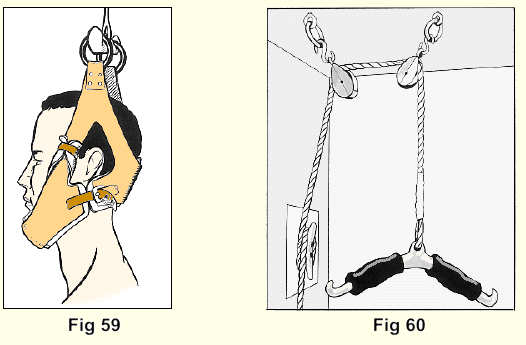

WITH TRACTION

The neck is best manipulated when the cervical spine is under traction. A strong head halter (Fig. 59) preferably made of leather, padded with removable sponge rubber, with a suspension apparatus (Fig. 60) is applied.

The first time the patient is suspended he may be anxious. He may be afraid of being hanged or strangled; so to begin with, only brief traction, about fifteen seconds, is applied. Later, many patients will hang their whole weight by their necks and even lift their feet off the floor.

Rotation:

With the patient's cooperation the head is rotated to one side as far as it will go. He is then asked to turn his head just a little more and the manipulation is completed by a short jolt through a small arc of movement. The head is rotated to the opposite side and the movement completed in the same way. In most patients a form of head lock is necessary to apply the great force that must be used. (Fig. 53). In smaller and lighter patients the manipulation may be completed by using the hands (Fig. 54).

When rotation is being applied, the nurse, with her hands on both of the patient's shoulders, pushes in the opposite direction from the rotation of the head (Fig. 61).

Posterior:

The operator uses both his thumbs to manipulate the spine posteriorly, one thumb being over the other, and by thrusting forward on the spinous processes one after another, the whole cervical spine is manipulated. While the posterior manipulation is carried out the nurse places both hands on the patient's forehead, or one hand on the forehead and the other on the chest, and thrusts backwards as the operator presses the spinous processes forward (Fig. 62).

Lateral:

The patient is removed from the traction apparatus and seated on a low stool. The procedure is carried out as previously described. It cannot be done when the patient is suspended in traction (Fig. 55).

LUMBAR SPINE

ON TABLE

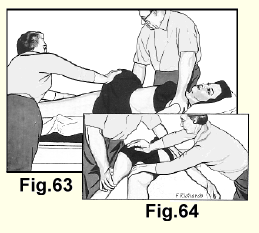

Rotation:

The patient is placed on the table face up. One thigh is flexed to a right angle. The shoulders are kept flat, while he is helped to rotate his pelvis. With one hand on the opposite shoulder and one hand on the knee, the operator applies several strong rhythmic downward thrusts on the knee. The nurse cooperates by synchronizing a firm shove on the upper buttock with each of these movements. The position is then reversed and the same procedure is carried out in the other direction (Fig. 63-64).

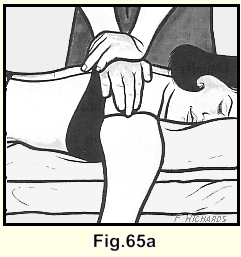

Posterior:

The patient lies face down. The doctor, with one hand over the other, applies a strong thrust on each of the spinous processes in the middle of the painful area in the lumbar spine. The sharp thrust over one particular spinous process will exacerbate the pain, and this spinous process, points at the intervertebral nucleus involved.

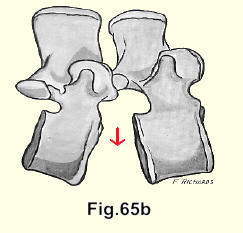

The spinous process belongs to the vertebra above the nuclear lesion. As a rule we proceed, while the patient is in this position, right up the dorsal spine (Fig. 65).

If there is radiation down one leg, that leg is passively extended as far as possible by the assistant (Fig. 66) and the patient is told to relax. Two or three additional sharp downward thrusts are applied to the low lumbar spine and lateral to it on the painful side. This is done in the belief that there may be an oblique erosion of the posterior annulus and that this thrust is more likely to disengage the fibrous mass. If a central erosion is suspected the assistant raises both legs together while the operator thrusts downward on the lower lumbar spinous processes (Fig. 67).

Usually the operator can feel a faint forward motion of the vertebra. Quite often a sharp forward movement can be felt and a distinct snap can be heard.

Lateral manipulation of the lumbar spine is difficult to do in a heavy patient and it is usually not possible to apply enough force to be effective, but we use it occasionally. The nurse raises the patient's legs up in the air and the operator thrusts down on the crest of the ilium (Fig. 68).

WITH TRACTION

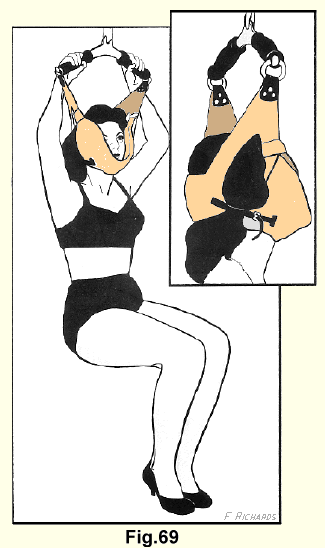

The patient is placed in the traction apparatus. The whole of the patient's weight is borne by the suspension apparatus, his hands grasp the crossbar, his feet only lightly touch the floor. The patient is told to let his low back relax (Fig. 69).

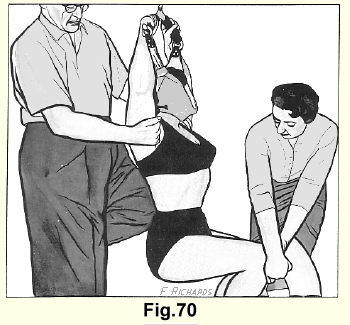

Posterior:

One of the operator's knees is placed over the spinous process at the point of maximum tenderness, his heel is braced against the wall. (The surface of the wall should be protected by a square of some durable substance.) He grasps the patient's shoulder and rocks him into extension several times. The nurse steadies the patient by applying counter-pressure to his knees (Fig. 70).

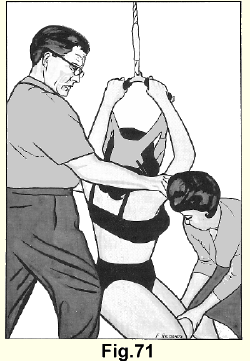

Rotation:

The patient is told to twist his shoulders around as far as he can to one side. The nurse applies counter-pressure to the knees. The doctor also applies counter-pressure by placing one knee against the patient's upper outer thigh as shown in Figure 71. When the limit of movement is reached, the manipulation is completed with a powerful thrust. The same procedure is carried out in the opposite direction.

We follow this by manipulation on the table, which is covered by a two-inch thick pad of sponge rubber. The previously described techniques of rotation and antero-posterior thrusts are used.

DORSAL SPINE

ON TABLE

Rotation:

The patient is placed face upwards on the table. One thigh is flexed to a right-angle. The pelvis is rotated. With one hand on the knee and one hand on the opposite shoulder which is allowed to lift a few inches off the table the operator applies several forceful downward thrusts on the knee and at the same time several backward thrusts on the shoulder. The nurse synchronizes a firm shove on the patient's upper buttock with each of these movements. The position is reversed and the same procedures are carried out in the opposite direction.

Posterior:

The patient turns over and lies face down on the table. The operator places the heel of one hand over a spinous process in the middle of the painful region and the other hand on top of it. In this way, a strong but controlled downward thrust can be made. Thus suddenly distracts the vertebral bodies anteriorly but does not close them posteriorly. The nucleus receives a sudden suction force which tends to displace it anteriorly, i.e. away from the sensitive area of the annulus. In the dorsal spine one can always feel, and hear the vertebral body jump forward. (Fig. 65B)

WITH TRACTION

Posterior:

The patient is placed in the traction apparatus with his hands grasping the rubber-covered cross bar. to relieve the pressure on his jaws. He should be placed low in a sitting position, so that the operator can get his knee against the spinous processes in the affected area. The shoulders are pulled back against the counter pressure of the knee three or four times in a rhythmic movement. The position is illustrated in Figure 70 but the operator's knee, of course, is in a higher position.

Rotation:

The patient's cooperation is again requested so that he may rotate his shoulders to one side as f ar as he can go. The nurse applies counter-pressure to the knees. The doctor also applies counterpressure by placing one knee against the patient's outer thigh as shown in Figure 71. When the limit of movement is reached, the manipulation is completed with a powerful thrust. The same procedure is carried out in the opposite direction.

On table (2):

The patient is then removed from the traction apparatus and the posterior and rotation manipulations are performed while he is lying on the table. The movements used in manipulating the dorsal spine are essentially the same as those used in manipulating the lumbar spine except that the operator's attention is concentrated on the painful area in the dorsal spine.

Once the patients have recovered from their initial fear of being hanged, strangled, or otherwise injured, they take quite a keen interest in the proceedings and often make sensible suggestions. They should be given a hearing. Over the years we have modified our apparatus and our techniques considerably as the result of patients' comments. It was suggested that some sort of rubber shock absorber might help ease the pressure on the teeth in the traction apparatus, so we secured the mouth props that are used in electric shock therapy. Some patients like them, others do not.

Sometimes patients will say that a certain motion does them good and that another motion does not. We follow their suggestions, for we invariably find that they are right.

Manipulation of the spine is neither arduous nor time-consuming. The office nurse can quickly learn to suspend the patient in the traction apparatus and to apply the various counter- tractions.

The acute cases respond promptly, but in cases with long histories the doctor must continue patiently and persistently as long as they continue to improve.

The patients cooperate cheerfully in treatment and at the beginning enjoy the few hours of relief they get, sufficiently to keep on coming.

The acute cases or the acute exacerbations are manipulated daily for two or three times. The long-standing cases are manipulated three times a week. In these, some improvement, even if only for an hour or two, will be noted at once by the patient and if the doctor persists he will find failure to be uncommon. Lack of improvement after a few treatments points tentatively at operation or an error in diagnosis, and it is an important diagnostic point.

This cartoon, which hangs in a treatment room, is the humourous reaction of our artist to his own treatment by spinal manipulation, It struck a sympathetic chord and for many years has amused other sufferers from nuclear lesions.

When patients suffering from nuclear lesions have recovered, they should be warned of the almost inevitable recurrences to which they are prone at any time. They are advised to avoid, as much as possible, flexing the spine; but a cough or sneeze, which is accompanied by a sudden and forceful, even if small, range of flexion, may cause an acute exacerbation. Patients must be instructed to attend their doctor at once when an exacerbation occurs. Two or three treatments as a rule are enough to move the fibrous nucleus away again from the posterior part of the annulus. The patient is relieved, and further wear and tear on the annulus is avoided.

It is a notable fact that patients who have been treated by traction and manipulation ever since their first attack, who promptly come for treatment whenever they have an exacerbation, do not come to surgery, because erosion of the posterior annulus has been largely prevented.

COCCYALGIA

Coccyalgia is almost always the result of a nuclear lesion in a low lumbar disc. The pain is radiating pain, and the tenderness which is sometimes present is the result of traction upon the sacrococcygeal ligaments by the protective spasm of the sacrospinal muscles. The low back pain is often slight at the time of examination.

Treatment is satisfactory in these cases no matter how long the pain may have been present. Usually a few treatments of traction and manipulation in the lumbar spine completely relieve the condition. If they do not, one or two extra-dural injections, plus traction on the traction table followed by manipulation, almost invariably will do so. I have not yet seen a case in which excision of the coccyx was indicated.

THE TRACTION TABLE

The traction table has proved a valuable adjunct in the treatment of nuclear lesions in the lumbar spine, particularly in cases in which recovery is slow. We also use it in extremely painful cases in which manipulation is not possible immediately, and in these cases as a rule, we do a sacral extra-dural injection prior to the traction.

Two strong wide harnesses made of heavy cotton are applied over large pads of one inch thick foam rubber. The thoracic harness is attached to the two hooks at the head of the table. The pelvic harness is. attached to a heavy spring-balance and pull is applied through the spring-balance by a wheel with a worm-drive axle (Fig 73).

Traction is applied and gradually increased for several minutes until the maximum the patient can easily tolerate is reached. This is maintained for half an hour or so.

Some patients who have been suffering severe pain go to sleep while under heavy traction (more than two hundred pounds) on the table. After removing the patient from the traction table routine manipulation is performed.

THE SACRAL EXTRA DURAL INJECTION

The indications for the extra-dural injection are:

1. The presence of lumbar pain too great to allow either traction or manipulation.

The general practitioner is often called to see a patient who is suffering his first attack of nuclear lesion pain in the lumbar spine. The patient may be lying on the floor afraid to move, as any motion of the spine causes agonizing pain. The doctor should be prepared to give such patients an extra-dural injection. The dramatic relief of pain confirms the diagnosis of a nuclear lesion.

2. In cases in which recovery is slow, but surgery is not definitely indicated.

3. In coccyalgia.

If one or two traction and manipulation treatments do not markedly relieve the patient's pain, one or two sessions of traction and manipulation immediately after the extra-dural injections will almost invariably do so.

The injection relieves the backache and the radiating pain in the legs. It has been demonstrated by the use of contrast media that the anaesthetic solution lies between the anterior surface of the dura and the spinal column, and it reaches up to about the level of the third lumbar vertebral body. If a weak solution (0.47c) is used, no anaesthesia occurs apart from the relief of pain. We conclude from this that only the branches of the nervi sinu vertebrales are anaesthetized. Mild saddle anaesthesia occurs with the 0.88%, solution that we use, though the patients as a rule are unaware of it.

The solution is made of 14 cc of 2% saline, and 11 cc of 2% anaesthetic solution. A mildly hypertonic saline solution is used to prolong retention of the solution in the spinal canal and to secure mild pressure on the posterior annulus of the lower lumbar intervertebral discs.

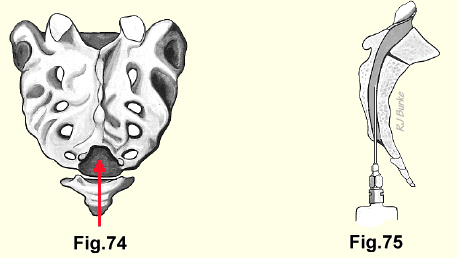

The patient is placed face down on an examining table. The tip of the coccyx, the sacro - coccygeal joint and the sacral cornua can be identified readily (Fig. 74).

A one-inch long hypodermic needle and 2cc of 2%, local anaesthetic solution are used to anaesthetize the skin, and the solution is also injected into the fibrous cover which closes the entrance to the sacral canal. After one has waited a few minutes for the anaesthetic effect, a No. 20, two and one-half inch needle, used with a 25cc syringe filled with the solution, is passed from the skin through the fibrous door to the canal and about two inches upwards (Fig. 75). The dural tube ends at the level upper surface of the first sacral segment, so there is little danger of giving an accidental spinal anaesthetic. The plunger of the syringe should be pulled back at intervals to make sure that the needle has not entered the dural tube or a blood vessel. The solution is then injected with steady pressure.

The injection is continued until the patient feels a mitigation of the low back pain and the radiating pain from which he has been suffering.

After two or three minutes he is free from pain and one may proceed with traction and manipulation, or traction upon the table.